What is Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)?

In depression, anxiety, PTSD, and OCD, certain regions of the brain do not communicate effectively with each other. TMS forces these brain regions to reconnect.

TMS uses pulses of a strong, focused magnetic field to make neurons fire. Neurons that fire together, wire together. Much like physical therapy for an injury, consistent TMS over several weeks restores the brain to more optimal connectivity.

TMS has been FDA-approved for routine clinical use since 2013. The magnetic field cannot be felt and the sensation of TMS pulses are similar to a finger tapping on the head. The most common side effect is mild headache which typically resolves quickly.

TMS is completely noninvasive, non-pharmaceutical, outpatient, and requires no assistant to come with the patient. You can drive in, receive TMS, and drive away immediately.

Safe for Baby and Mom

TMS is safe for pregnant and breastfeeding women with no pass-through effects on your baby.

Childcare is difficult and shouldn’t be a barrier to getting TMS. You can bring your little one with you. In between TMS sessions during your visit you can rest, listen to music, nurse, play – whichever is most comfortable for you.

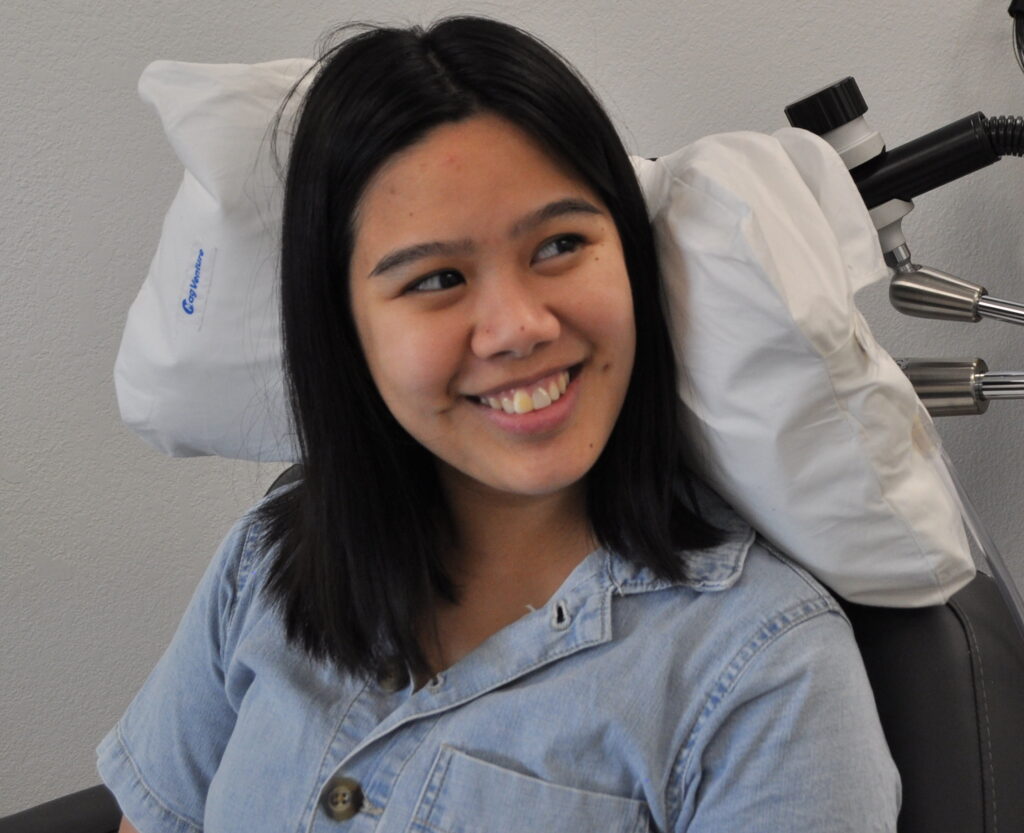

FDA-Approved for Adolescents (15+)

TMS is safe and effective in adolescents. The majority of patients across several clinical trials achieved clinically significant improvement in symptoms.

Now is the time to strengthen the mental health and resilience of our kids.

In a large sample of 562 adolescent patients, improvement in symptoms and remission were significantly higher in the TMS groups compared to controls, with no statistically significant difference in adverse events (side-effects). A separate review of 393 adolescent patients confirmed these findings. See FAQ below for references.

Frequently Asked Questions

As we are a nonprofit clinic, services are provided at cost – about the typical copay of a doctor’s visit. Our mission is accessibility. A human being should not have to move back in with relatives and take out a loan just to seek relief from suffering. We believe price gouging violates the profession of healing’s prime directive: Do no harm.

Yes, most major insurances cover TMS after certain prerequisites are fulfilled. The prerequisites typically involve having tried several antidepressants previously without success.

Compassion Neuroscience does not take any insurance at this time. However, we are in the process of credentialing with several carriers.

TMS can be painful, although most patients report it to be tolerable with an average reported pain rating of 3.5/10. The stimulation location, protocol type, and stimulation intensity greatly influence how comfortable TMS is. For instance, a 1 Hz (1 stimulation every second) protocol commonly used for anxiety is so gentle, many patients drift to sleep. On the other hand, the intermittent theta burst protocol we commonly use for depression can be intense for some. However, we slowly ramp intensity and the patient is in control at all times.

Because the stimulation pulse can also “catch” neurons in the muscles that enervate the scalp, eye, face, and jaw, slight twitching can occur during stimulation. However, this twitching is typically not painful and immediately ceases when stimulation is complete.

The most common side-effects of TMS are mild headache, typically resolving in a few minutes, and discomfort at the site of stimulation.

The most recent, comprehensive safety review describes the very low rates of adverse events (side-effects) over hundreds of thousands of TMS sessions:

Rossi, S., Antal, A., Bestmann, S., Bikson, M., Brewer, C., Brockmöller, J., Carpenter, L. L., Cincotta, M., Chen, R., Daskalakis, J. D., di Lazzaro, V., Fox, M. D., George, M. S., Gilbert, D., Kimiskidis, V. K., Koch, G., Ilmoniemi, R. J., Pascal Lefaucheur, J., Leocani, L., … Hallett, M. (2021). Safety and recommendations for TMS use in healthy subjects and patient populations, with updates on training, ethical and regulatory issues: Expert Guidelines. In Clinical Neurophysiology (Vol. 132, Issue 1, pp. 269–306). Elsevier Ireland Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2020.10.003

There is a vanishingly small risk of seizure, about 1 in 32,592 according to this comprehensive study:

Taylor JJ, Newberger NG, Stern AP, Phillips A, Feifel D, Betensky RA, Press DZ. Seizure risk with repetitive TMS: Survey results from over a half-million treatment sessions. Brain Stimul. 2021 Jul-Aug;14(4):965-973. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2021.05.012. Epub 2021 Jun 13. PMID: 34133991.

Absolutely not. They are completely different technologies.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) or “shock therapy” is an inpatient procedure in which the patient goes under anesthesia and electric current is used to cause a seizure. It is an intensive procedure with profound side effects such as memory loss and is reserved for the most severe cases of depression.

TMS on the other hand, uses a focused magnetic field to selectively activate regions of the cortex to gradually influence connectivity changes over time.

Accelerated protocols condense previously defined protocols into a shorter time window. The original FDA-approved protocol for depression requires 1 TMS session per day, 5 days per week, over 6 weeks for a total of 30 sessions. The accelerated protocol we typically use is 3-4 sessions per day, with a rest period between each session, over 10 consecutive days for a total of 30-40 sessions.

Daily visits over a 6 week period is a major burden and difficult to arrange with work and family responsibilities. Accelerated protocols seek to make that time commitment easier to manage while maintaining the same efficacy of treatment.

Accelerated protocols are a major focus of current research:

van Rooij, S. J. H., Arulpragasam, A. R., McDonald, W. M., & Philip, N. S. (2023). Accelerated TMS – moving quickly into the future of depression treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology, February, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-023-01599-z

Tang, N., Shu, W., & Wang, H. (2023). Accelerated transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depressive disorder: A quick path to relief? WIREs Cognitive Science, August. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1666

Batail, J.-M., Xiao, X., Azeez, A., Tischler, C., Kratter, I. H., Bishop, J. H., Saggar, M., & Williams, N. R. (2023). Network effects of Stanford Neuromodulation Therapy (SNT) in treatment-resistant major depressive disorder: a randomized, controlled trial. Translational Psychiatry, 13(1), 240. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02537-9

Buddy TMS is partnering up with a family member, friend, or battle buddy to do a TMS series together. In our accelerated protocols, there is a rest period of approximately 30 minutes. This affords the opportunity to alternate a person receiving treatment and a person in the rest period, without extending the overall time required.

The operational cost to our clinic is based on time required, not the number of people in the room. So just like splitting a cab, you can split the cost of a TMS series. For safety and practicality, the limit is 2 people. We take HIPPA and protected health information very seriously. Please keep in mind that whomever you do Buddy TMS with may hear your conversations with treatment staff.

Peer-reviewed research published in scientific journals:

Koo M. The potential of transcranial magnetic stimulation as a treatment for depression during pregnancy. Brain Stimul. 2023;16(3):734-736. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2023.04.005

Miuli A, Pettorruso M, Stefanelli G, et al. Beyond the efficacy of transcranial magnetic stimulation in peripartum depression: A systematic review exploring perinatal safety for newborns. Psychiatry Res. 2023;326(January):115251. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115251

Al-Shamali H, Hussain A, Dennett L, et al. Is repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) an effective and safe treatment option for postpartum and peripartum depression? A systematic review. J Affect Disord Reports. 2022;9(February):100356. doi:10.1016/j.jadr.2022.100356

Kim DR, Wang E, McGeehan B, et al. Randomized controlled trial of transcranial magnetic stimulation in pregnant women with major depressive disorder. Brain Stimul. 2019;12(1):96-102. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2018.09.005

Hızlı Sayar G, Ozten E, Tufan E, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17(4):311-315. doi:10.1007/s00737-013-0397-0

Kim DR, Wang E. Prevention of supine hypotensive syndrome in pregnant women treated with transcranial magnetic stimulation. Psychiatry Res. 2014;218(1-2):247-248. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.04.001

Kim DR, Sockol L, Barber JP, et al. A survey of patient acceptability of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) during pregnancy. J Affect Disord. 2011;129(1-3):385-390. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.027

Kim DR, Epperson N, Paré E, et al. An open label pilot study of transcranial magnetic stimulation for pregnant women with major depressive disorder. J Women’s Heal. 2011;20(2):255-261. doi:10.1089/jwh.2010.2353

Peer-reviewed research published in scientific journals:

Li Y, Liu X. Efficacy and safety of non-invasive brain stimulation in combination with antidepressants in adolescents with depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15(February). doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1288338

Sun C-H, Mai J-X, Shi Z-M, et al. Adjunctive repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for adolescents with first-episode major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14(August). doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1200738

Croarkin PE, MacMaster FP. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Adolescent Depression. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2019;28(1):33-43. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2018.07.003

Allen, C. H., Kluger, B. M., & Buard, I. (2017). Safety of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Children: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Pediatric Neurology, 68, 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2016.12.009

Wall CA, Croarkin PE, Maroney-Smith MJ, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Guided, Open-Label, High-Frequency Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Adolescents with Major Depressive Disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(7):582-589. doi:10.1089/cap.2015.0217

Croarkin PE, Rotenberg A. Pediatric Neuromodulation Comes of Age. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(7):578-581. doi:10.1089/cap.2016.0087

Krishnan, C., Santos, L., Peterson, M. D., & Ehinger, M. (2015). Safety of Noninvasive Brain Stimulation in Children and Adolescents. Brain Stimulation, 8(1), 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2014.10.012

Donaldson AE, Gordon MS, Melvin GA, Barton DA, Fitzgerald PB. Addressing the Needs of Adolescents with Treatment Resistant Depressive Disorders: A Systematic Review of rTMS. Brain Stimul. 2014;7(1):7-12. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2013.09.012

Wall CA, Croarkin PE, Sim LA, et al. Adjunctive Use of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Depressed Adolescents. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(09):1263-1269. doi:10.4088/JCP.11m07003